7 Revealing Findings from a First-of-Its-Kind Map and Analysis of American LGBTQ Bars

Some Americans have to travel 500 miles to the nearest gay bar. Others can access a dozen within a 15-minute walk.

Nightlife has long been a tool for queer communities in America to find each other, celebrate identity and feel accepted. In rural and urban areas alike, gay bars provide an enlightening—if imperfect—window into understanding the health and culture of America’s LGBTQ population.

As anti-trans legislation and threats to marriage equality mount, many queer Americans are flocking to shield states with greater legal protections. For some, finding the nearest gay bar serves as a first step to finding community in their new homes.

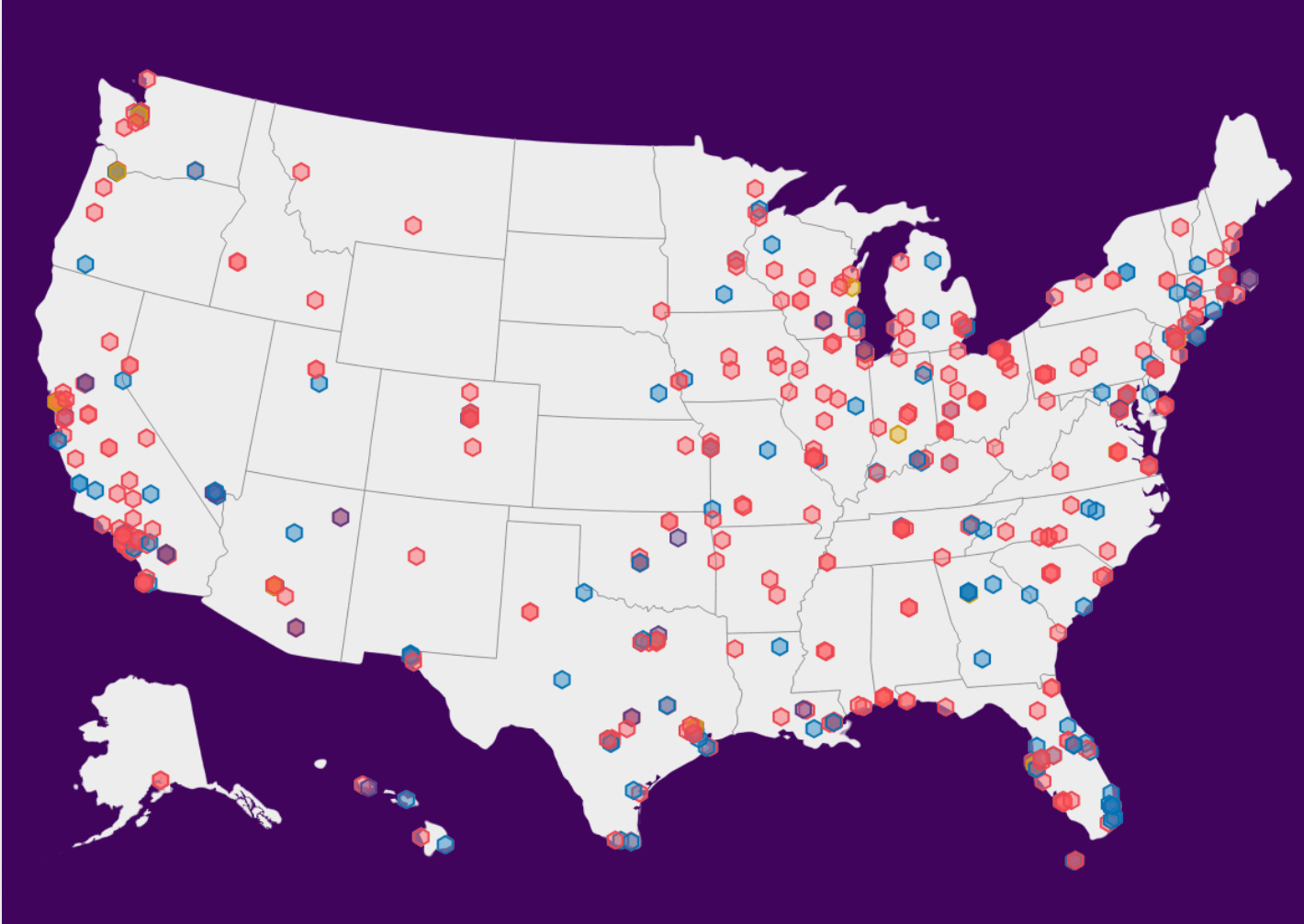

In a first-of-its-kind analysis, Uncloseted Media mapped every single LGBTQ nightlife location in the U.S. The data is based on a 2023 census of gay bars and clubs by sociologist and Oberlin College professor Greggor Mattson and was updated in 2025 by Columbia Journalism School graduate students Dan O’Connor and Tory Lysik1.

The findings reveal unexpected trends that inform us about the state of the American gay bar and—more broadly–queer culture in the U.S. Here they are:

1. There are gay bars in every state except Wyoming and North Dakota

Unsurprisingly, states with large cities tend to have the most LGBTQ nightlife. California takes the top spot with 128 gay bars and Texas comes in at a distant second with 67.

New York is third, with 61 bars, followed closely by Florida’s 59 bars. Illinois rounds out the top five with 40 bars.

Montana, South Dakota, Kansas, New Mexico and Vermont have just one gay bar. Wyoming and North Dakota have none. For someone in northwestern North Dakota, it would take over 7 hours of driving across roughly 500 miles to reach Club David, the nearest gay bar in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. If they have a passport handy and are short on time, they could make the four-hour trek north of the border to Q Nightclub and Lounge in Regina, Saskatchewan.

For Wyoming, advocates say the state’s conservative values are not the main reason there’s no gay bar. Quite simply, demand is limited in a state of half a million people spread out over almost 100,000 square miles, Sara Burlingame, who serves as Wyoming Equality’s executive director, told Uncloseted Media.

Despite this, she says there are still options. Bars in Laramie, the state’s main college town, host occasional drag nights and other queer-focused events. Other people leave the state entirely, flocking to Salt Lake City or Denver.

“For generations, if you were LGBTQ and you didn't want the struggle of the legislature fighting over whether you should have rights or not, or churches preaching against you, or someone who was raised to believe that they should be violent towards you … You graduated high school, and then you got the hell out of dodge,” says Burlingame. And when queer people leave, demand for gay nightlife declines further.

2. When you control LGBTQ nightlife per capita, different results emerge

D.C. has the most gay bars per capita, with 13 bars serving a population of slightly more than 1 million residents.

Delaware comes in second, with roughly 700,000 residents and six bars, four of which are in the resort town of Rehoboth Beach, a popular gay travel destination.

Hawaii, with 5.53 gay bars per million residents, comes in third. The islands blend the classic gay bar with Indigenous Polynesian motifs. Hula’s Bar and Lei Stand is one of the state’s eight gay bars and has served locals and tourists alike for over 50 years.

Rhode Island comes in fourth with 5.39 gay bars per million people, and Louisiana rounds out the top five.

In addition to Wyoming and North Dakota, there are six states with fewer than one gay bar per million people. Alabama, with 5 gay bars, has just 0.97 bars per million people. New Jersey, just outside two of the country’s largest queer nightlife hubs in New York City and Philadelphia, has just 0.53 bars per million residents. And Kansas comes in last place with just 0.34 gay bars per million residents.

3. Most bars are in urban areas, but don’t count out rural queers

Mapping the bars by county shows a concentration around the largest cities. Los Angeles County, New York County (Manhattan) and Cook County (Chicago) stand out. But so do counties with smaller cities, including Columbus, El Paso and Salt Lake.

266 of the country’s 750 gay bars were in the 20 most populous counties. That means roughly 35.5% of the nation’s gay bars exist in an area with just 18.5% of the U.S. population.

The map reveals that there are large swathes of the Mountain West that lack any dedicated spaces for gay nightlife. Stathis Yeros, a historian and designer who has traveled the country researching queer spaces, says rural LGBTQ folks are used to this and are willing to drive long distances to visit a queer watering hole.

“What I have found in the places I visited is that [the] separation between urban and rural doesn't quite exist in a big part of the U.S.,” he says. “You can go to an event in Atlanta, and you can go back to your house in the outskirts of Birmingham.”

4. In big cities, neighborhood bars struggle to compete with gayborhood bars

Even in areas famous for their nightlife, access to queer spaces can be uneven. Only three of New York City’s five boroughs have a single queer bar.

Manhattan, with its storied gayborhoods like the West Village, Chelsea, Hell’s Kitchen and Harlem, is home to 36 gay bars. In Hell’s Kitchen, a 15-minute walk with only small detours away from 9th Avenue could bring you past 10 gay bars.

Brooklyn is home to five gay bars, and Queens has four, but the Bronx and Staten Island have zero. When the Bronx lost its last gay bar in 2023, its owner told the Bronx Times, “It’s just difficult when you’re up against Manhattan.”

The Manhattan pull may explain New Jersey’s small gay bar scene. The state has two gay bars in Jersey City, one in suburban Bergen County and two on the shore.

Similar patterns can be seen in Chicago and Los Angeles, with nearly all of Chicago’s gay bars in the city’s Northeast, while Southern California has clusters in West Hollywood, Long Beach and Palm Springs.

“Gay bars have been concentrating,” says Greggor Mattson, the sociologist whose team first collected the census data on gay bars nationwide. “Think about the possibilities of barhopping versus going to a single bar.”

5. Blue states tend to have more gay bars, but the correlation is not strong

While an imperfect measure of a state’s political leaning, there is a moderate correlation between Kamala Harris’ 2024 presidential vote share and the number of gay bars. D.C., where Harris got just over 90% of the vote, has the most gay bars for its population. And she earned the smallest vote share in bar-less Wyoming.

But the data also reveals several hotspots in conservative states. Ohio, which voted 55% for Trump in 2024 and swung red, has 33 gay bars and beet red Louisiana has 22 bars, mostly around New Orleans.

That suggests little impact of party politics on gay bars, even though 86% of LGBTQ voters cast their ballot for Harris, according to one exit poll.

6. Lesbian bars and POC-focused queer bars are harder to find

Many bars continue to draw crowds of white gay men, while bars catering to people of color (POC), queer women and trans folks are rare.

“There are now individuals, increasingly, who identify as LGBTQ+ who don't necessarily feel safe or empowered or that they are with others like themselves when they walk through the doors of a gay bar,” says Amin Ghaziani, an urban sexualities researcher at the University of British Columbia.

Mattson’s data found that while 66% of LGBTQ bars appear to cater to both men and women, 24% cater primarily to men.

Bars catering mostly to queer women are rare. Per 2025 numbers from the Lesbian Bar Project, there are 36 lesbian bars across the country—that’s just 4.8% of all queer bars. And per Mattson’s data, just 6.6% of queer bars catered to POC.

7. Bars are important—but there’s so much to queer culture

Those without a gay bar in town don’t necessarily need a watering hole to find community. Every August in Wyoming, over 500 queer people from across the Mountain West flock to Medicine Bow National Forest for “Rendezvous,” a five-day LGBTQ campout.

Burlingame of Wyoming Equality says the unique character of her state’s queer community sometimes surprises outsiders given its overlap with the area’s outdoorsy and gun-toting culture. “LGBTQ Wyomingites are still Wyomingites,” she says.

Queer communities across the country are shaped by politics, geography, distinct histories and circumstances, making nationwide generalizations impossible. Yeros, who has spent time researching queer spaces in the South, emphasizes that each community has its own story.

“What happens in Atlanta is not necessarily the same as what happen[s] in New Orleans,” he says. “It's certainly not the same as what happens in San Francisco or New York or Chicago.”

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button:

The data was initially collected in 2023 by a team of researchers at Oberlin College led by Greggor Mattson. The team used Damron Guides, a historic gay travel guide, as well as online listings to create a census of gay nightlife spots nationwide. This data was analyzed for research on the character of gay bars and was published in June 2023.

To determine what counted as a gay bar, the researchers checked reviews and online listings. Those that appeared to be considered gay bars by the local community were also counted, according to Mattson.

The data, courtesy of Mattson, was then checked by data journalists Dan O’Connor and Tory Lysik and updated in early 2025. Bars that appeared to have closed since April 2023 were removed from the data. The data does not include bars that have opened in the past two years.

While this data aims to illustrate the state of LGBTQ nightlife nationwide, some errors are likely. Some bars may not be included if they were missed in the original coding process, removed erroneously, or opened recently.