How RuPaul's Drag Race Became A Beacon of Survival And Queer Liberation

As RPDR enters its 17th season with 29 Emmys under its belt, Uncloseted spoke with Alaska and Shea Couleé, as well as academics and superfans, to investigate how the show has affected U.S. culture.

Editor’s note: This article includes mention of suicide. If you are having thoughts of suicide, or are concerned that someone you know may be, resources are available here.

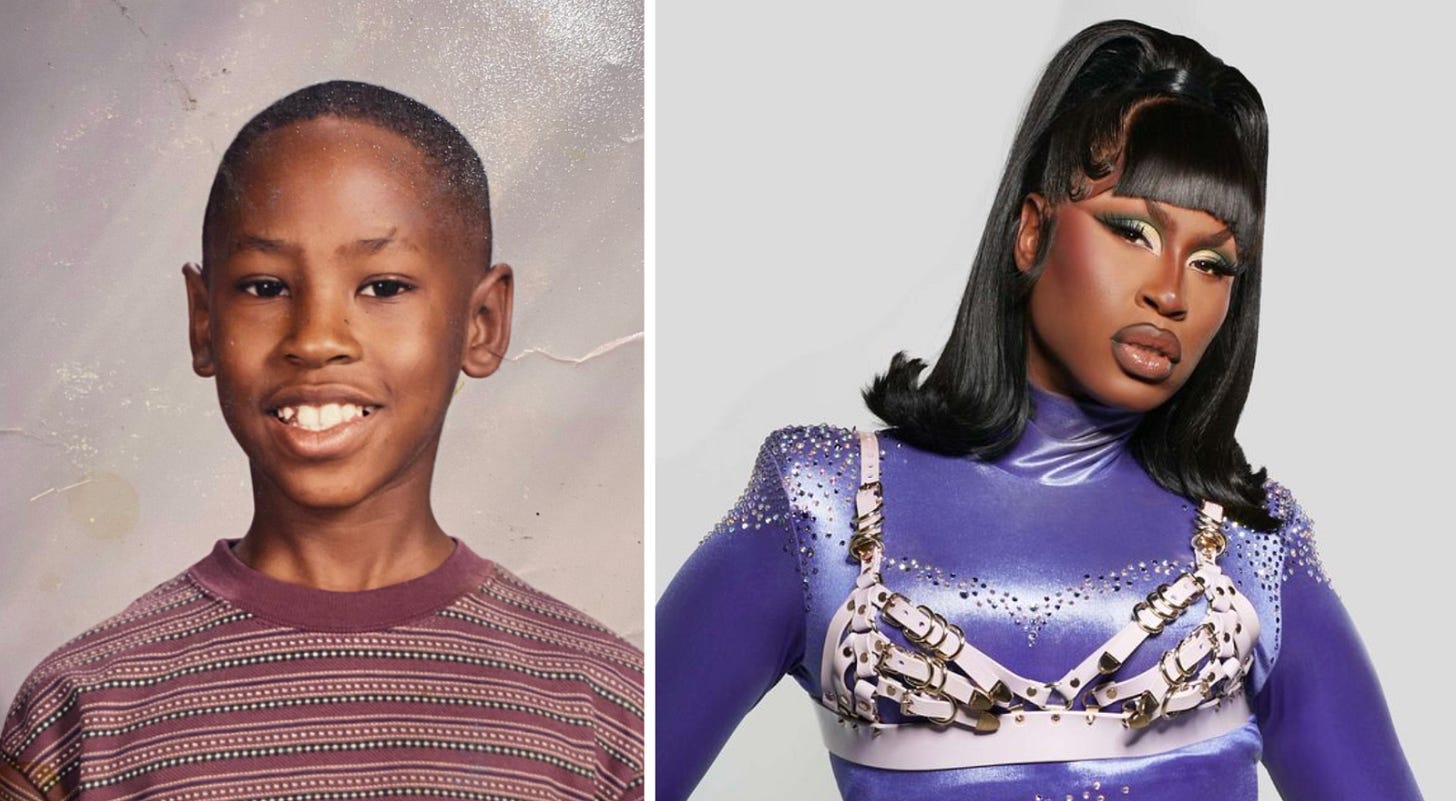

At five years old, Justin Andrew Honard remembers discovering the treasures of his grandmother’s closet in Erie, Pennsylvania. He doused himself in her perfume, wrapped himself in her delicate furs, and twirled in her fancy skirts.

“I was very drawn to the clothes,” Honard, better known by his drag queen stage name Alaska Thunderfuck 5000, told Uncloseted Media. “They were more fun than what I was allowed to wear in my everyday life.”

But she says that sort of freedom of expression was short-lived. “I quickly realized I can't be doing that because it's not safe.”

“There was no representation [in Erie],” says Alaska, who is currently starring in “Drag: The Musical.” “Queer people were treated as other. You don't have to be told explicitly that you are being othered and you need to be careful. I knew that. Getting called a f*ggot, well that was just part of walking through life.”

Alaska says she found her sense of belonging when she discovered drag in college. “It just made sense to me. I got to decide what kind of character I wanted to be and what kind of stories I wanted to tell.”

Three decades after playing with her grandma’s clothes, Alaska catapulted to drag superstardom when she appeared on season five of “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and leveraged her initial popularity as a fan favorite to return and win season two of “RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars.”

Alaska is far from alone when it comes to finding superstardom on RPDR. After the Jan. 3 season 17 premiere, 224 queens will have appeared on the American reality competition show. The U.S. version of “Drag Race” has won 29 Emmys, more than any other reality show ever. And the franchise has spawned 15 international installments featuring hundreds of additional queens from Canada, Thailand, Brazil, the United Kingdom, Belgium and beyond.

RPDR has not only moved the needle forward for representation on television; it has shattered the one-dimensional depiction of queer people that Americans had become accustomed to and has tackled tough LGBTQ-themed topics that had never been addressed on television. “We had “Will & Grace,” we had “Ellen,” but RuPaul took it to another level,” says Joe E. Jeffreys, a drag historian who teaches a course called “RuPaul’s Drag Race and Its Impact” at The New School.

THE IMPACT OF QUEER REPRESENTATION ON MENTAL HEALTH

“It presents a cornucopia of identities for people they may never have seen,” Jeffreys told Uncloseted Media. “All sorts of queer people in front of us, all sorts of body types, all sorts of gender identities.”

“[The show] is about watching people live their authentic truth. It’s a story of people who have lived through pain or trauma and legislation telling them that they shouldn't exist, expressing themselves joyfully and beautifully and hilariously. That is life-affirming for everybody,” says Alaska, noting that there are more than 500 anti-LGBTQ bills sweeping through state legislatures right now.

“It saved my life,” says 27-year-old Jani Aldinor, a trans man who started watching “Drag Race” at 11 years old when the show first premiered.

“The show gives me an outlet to see LGBTQ people thriving not despite of but because of their queerness,” Aldinor, who grew up in the 6,900-person town of Willis, Texas, told Uncloseted Media. “It gives me so much joy. It was my comfort when I was going through my most depressive episodes and is a big contributor to how I deal with my depression.”

Last year, Aldinor’s depression was at its worst. “I just thought about taking my life a whole lot. But then I started thinking about all the things I loved. One of the things that would pull me out of it would be, ‘But if I die, I can't go on Reddit and discuss the new season of “RuPaul's Drag Race.’’”

It may seem hard to credit a reality show as a resource to help someone with their mental health, but a 2020 GLAAD study found that authentic representation affirms LGBTQ individuals, while a lack of media representation perpetuates harmful stereotypes, lowers self-esteem, hinders access to support, and increases risks of mental health challenges.

These effects can be particularly meaningful for LGBTQ youth in America, 41% of whom considered suicide in the last year—three times more than their heterosexual peers. “[Seeing representation] can have an uplifting and hopeful effect. Seeing people who have survived, that means that they can do it, too,” says Jeffreys.

“There's so many things against me,” says Aldinor. “I'm trans, I'm Black, Haitian, poor, disabled, I was set up to fail. Sometimes I would think, ‘There's no way I'm going to make it.’ Seeing people on the show rise above those inherent disadvantages creates a sense that there's a chance that you're going to be okay. It gives me an enormous amount of hope.”

Aldinor says he saw himself in Love Masisi, a Haitian queen who appeared on Drag Race Holland. “Seeing how she thrives as a drag queen opened my heart. Haitians don't get positive press at all. So seeing Haitians thrive and then adding on the aspect of being queer, being gender nonconforming, that was just so joyful to me.”

“There are so many ways that the fans connect to the stories on the show,” says Shea Couleé, winner of “RuPaul’s Drag Race: All Stars” season five. “Intersectionality is about how we combine all our lived experiences to contribute to who we are,” Couleé, who is Black and nonbinary, told Uncloseted Media.

“The show offers enormous progress for the queer community,” says Niall Brennan, media scholar and gender and sexuality researcher at Fairfield University. “Without RuPaul's Drag Race, there would be a vacuum of voice and representation and identity and performance of queerness.”

TACKLING TOUGH TOPICS

Beyond multiple representations of queerness in its cast members lies the themes that the show explores. In each episode, one queen typically talks about a trauma they went through or a hurdle they had to overcome. Memorable moments include Katya discussing her drug addiction and how she got clean; Trinity The Tuck talking about how she performed at Pulse Nightclub the week before the mass shooting that killed 49 people; and Shea Couleé discussing their struggle with body image.

“Sometimes people don’t understand that though we come across as these strong, beautiful creatures that sometimes we’re really struggling on the inside,” Couleé shared with their fellow contestants.

Perhaps the most memorable moment came on season one, when Ongina, a Filipino-American queen, opened up about being HIV-positive. “I didn’t wanna say it on national TV because my parents don’t know,” Ongina told the judges through tears. “You have to celebrate life. You keep going. And I keep going,”

RuPaul, known as MamaRu to the queens, responded by telling Ongina: “You are an inspiration. You are a survivor. And baby, you are still in the race. I love you sweetheart.”

THE POLITICIZATION OF THE RUNWAY

Beyond these conversations, the show is intensely political. In 2021, shortly after the murder of Geroge Floyd and in the midst of the Black Lives Matter movement, Symone, the season 13 winner, wore an all-white dress that constricted her body in a way she said "represent[ed] what it can sometimes feel like to be of color in our country.” She designed red crystal-studded bullet holes across her back with the words "Say Their Names" painted in red to symbolize blood as she spoke the names of murdered Black Americans: “Breonna Taylor, George Floyd … Trayvon Martin, Tony McDade … and Monika Diamond.”

On season 12, Jackie Cox became the first queen to don a Muslim-inspired outfit when she wore a star-spangled hijab that nodded to her American and Muslim identity in what became known as one of the most politically powerful fashion moments in the show’s history.

One year later, Gottmik, the first trans man to compete on the show, walked the runway nearly naked, with only nipple pasties and a miniature black dress covering their private areas. This was in part to show his body after top surgery, saying he wanted to pay “homage to all of the trans women that have inspired me and showed me that drag is for everyone.” The performance stoked controversy in conservative circles, with Megyn Kelly posting Gottmik’s look on X and commenting: “This whole ideology is sick.”

Couleé, who was deeply inspired by Gottmik’s performance, says “everything” they do in drag is political. “Every time I put on my lashes. Being a Black, queer, gender nonconforming individual who has been on an international platform three times showcasing my identity is radical in and of itself,” they say.

“There are so many politicians and people who paint us out to be perpetrators of harm toward children and it’s simply not true. So the fact that I get to show my authentic self, that’s what feels radical to me because I am going up against the status quo every time I do drag.”

Couleé is one of the many queens who has called out President-elect Donald Trump and the GOP for spending over $215 million on anti-trans ads this election cycle and for spewing anti-trans rhetoric like saying we need to get rid of “transgender insanity.”

“Anyone who would not support me because I don’t like Donald Trump was not a fan to begin with and isn’t someone I would want in my stratosphere,” says Couleé. “I don’t give a flying f*ck, excuse my language, about some insidious, insecure man who has nothing but ill will toward the community. He’s a baby. He’s a man child.”

DRAG QUEENS: THE AMBASSADORS OF BEING YOURSELF

For many viewers, and particularly those who grew up in rural areas or in states where queer rights are under attack, RPDR and the queens on it have helped them come to terms with their LGBTQ identity in life-saving ways.

“Just seeing people being happy and being who they are is life-affirming,” Earle Ratcliffe, a 46-year-old from rural Canada, told Uncloseted Media. “I figured out I was gay when I was 11, but I didn’t want to be “too gay.” Seeing people on Drag Race that can unapologetically be themselves, well I started thinking, maybe I can be that too.”

Clint Martin, a 43-year-old software developer who grew up in a Mormon family in rural Alabama, felt like that gay community was “foreign.” After coming out in his thirties, he says the show helped him validate his identity and explore his expression of gender. “It helped me with subtle things, like being okay with my voice going higher, or with sitting in chairs in a more relaxed way,” he says. “It gave me additional tools to rediscover parts of myself and realign parts of myself that I had locked away a long time ago.”

RPDR SASHAYS INTO AMERICAN LIVING ROOMS

“RuPaul’s Drag Race” originally aired in 2009 on Logo TV, a niche LGBTQ broadcast channel. But as it exploded in popularity, it moved to VH1 in 2017, and eventually to MTV in 2023, where it now airs in primetime. According to Nielsen data, last season’s premiere was the top cable entertainment telecast of the day within the coveted 18-49 age demographic.

“It's important to make the distinction between representation that happens within the community and that happens in mainstream media,” says Michael Bronski, professor of media and activism at Harvard University. “What's amazing about RuPaul is that he brought representation of drag into the mainstream.”

Jeffreys says that a majority of the viewership is women, usually married and with kids. “It can give [people who are not in the LGBTQ community] a way to understand.”

Studies show that when people are exposed to LGBTQ characters authentically, they are more accepting than those not exposed to LGBTQ media, leading to a deeper connection and comfort with queer people in their daily lives.

“RuPaul didn't want this to just be another reality show,” says Alaska. “She wanted it to be something that touches on the uncomfortable parts of life and the difficult parts of people's stories and I think she achieved that.”

“The show speaks to the dreamer,” Rupaul said in a 2019 CBS interview. “Our show helps young people navigate some tricky waters. These kids on our show, they have been through everything ... There are dangerous things that come along with following your heart … We wanted to include the full experience of being an outsider.”

RPDR returns to American screens for its 17th season on Jan. 3, and millions of viewers will be tuning in. Queer bars will be packed with hundreds of LGBTQ viewers (like the Superbowl, but make it queer) who will be watching the next generation of drag queens take to the stage for the first time.

Aldinor, who never misses an episode, fondly recalls finding the show at 11 years old in his mother’s bedroom in rural Texas.

“I’ll never forget when I sat down and watched with my mom,” he says. “I saw Ongina speaking and I thought the name Ongina was so funny, and she looked so fabulous and that just took me. I didn’t have anything LGBTQ in my life, and the colors, the makeup, the clothes, the people, it was a whole new world for me.”

As millions of LGBTQ kids across the country struggle with mental health and acceptance, RPDR has created a community of refuge for many of them trying to find identity. This includes one of the nearly one million members of the RuPaul’s Drag Race subreddit who wrote about how the show saved their life.

“Before coming to terms with my sexuality, I started watching “Drag Race” and I was in quite a dark place. I used to think, ‘I would rather be dead than gay.’ But hearing the stories from the queens and how they came to terms with things gave me the strength to acknowledge who I was and slowly, I found peace … Drag does truly save lives and for that, I will forever be thankful.”

Additional reporting by Sophie Holland.

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button: