Why Lesbians Face a Maternal Healthcare Crisis

Eighty-three percent of queer women reported birthing complications. From systemic bias to outdated medical policies, lesbians face a maternal health system that was never designed with them in mind.

In January, a lesbian couple from New Jersey had a labor playlist picked out, electronic candles ready to go and an “atmosphere” they wanted to create while birthing their first child. They were eager and “not at all worried.”

But Amy and Jessica say their plans for a smooth birth went out the window when a routine check-up turned into a harrowing eight-day hospital stay. “It was awful. It was horrendous,” Amy, the birthing mother, told Uncloseted Media.

At 37 weeks pregnant following in vitro fertilization (IVF), the couple, who asked to use pseudonyms because they are considering litigation against the hospital, was told that the birthing mother needed to have her labor induced immediately due to high blood pressure. After three days of failed induction, doctors performed an emergency C-section during which she hemorrhaged and lost four liters of blood. The doctors eventually had to remove her uterus to “save her life.”

“We did research later and found out that induction medication and IVF both increase the risk of hemorrhage. It just felt like no one was listening to us or informing us,” says Jessica.

“If pregnancy were a men's health field, this wouldn't be happening,” Amy says. “You think of medicine now and it's so modernized and there are so many technologies, but there is something so lacking in women's health care.”

According to a 2022 study in the Association of American Medical Colleges, more than half of queer women reported that the quality of their experience with pregnancy, birth and postpartum care was impacted by bias or discrimination, compared to 35% of heterosexual people. In addition, 83% of queer women reported birthing complications compared to 63% of their heterosexual counterparts. Queer women also have higher rates of stillbirths, miscarriages and premature births.

“Female-bodied people have been ignored in medicine for so long, and taking on the queer identity makes it worse,” says Marea Goodman, midwife and founder of PregnantTogether, an LGBTQ-focused midwife practice. “Clinics arose out of a need to support heterosexual people who are experiencing infertility and for many years queer folks were barred from accessing fertility care. They're just not for creative family structures.”

The Healthcare System Was not Built for Queer Women

While roughly 59% of bisexual women and 31% of lesbians give birth in their lifetime, bringing tens of thousands of babies into the world each year, the healthcare system is hard for them to navigate.

A 2022 study found that LGBTQ couples are more afraid of childbirth than heterosexual couples. And it’s not just the pregnancy itself that is scary. According to Anna Malmquist, one of the authors of the study and a researcher at Sweden’s Linköping University, there are many concerns queer women face when walking into a hospital.

“‘What if they misgender me?’” she says. “‘What if they don’t recognize my partner as my partner? What if they don't respect my pronouns? I cannot just go away and seek care somewhere else, because the baby has to come out.’ So the minority stress becomes a second layer added to these bodily fears.”

One reason queer women may face these concerns is that medical school curricula often fall short in teaching prospective physicians about LGBTQ reproductive health.

One study reported that the median instructional time on all LGBTQ topics was just 11 hours across four years, with many programs failing to address disparities faced by lesbian patients in accessing prenatal care and family planning services. In a 2021 study, half of OB-GYN residents reported feeling unprepared to care for lesbian or bisexual patients and 92% desired more education on how to provide healthcare to LGBTQ patients.

This lack of education can result in queer women feeling out of place. “Walking down the halls of my clinic, all of the stock art of couples was white and heterosexual, nothing queer, and the literature all said ‘mom and dad,’” says Angela Thompson, a Verizon IT tech from Columbia, South Carolina.

Alyssa and Sam Darling delivered their first child in 2019 in Los Angeles.

When they went back to the delivery ward after the birth to do a routine check-up with their child, one of the nurses at the door stopped Alyssa, the non-birthing partner.

“She physically put her hand on my chest and stopped me, and said, ‘It’s parents only,’” she remembers. “The baby was my eggs, so biologically mine. … It was just so confusing. … We were exhausted, we just wanted to go home, and it was the last thing we wanted to deal with.”

“It’s like you're having to come out time and time again,” Sam adds. “And for some people, that can be extremely triggering.”

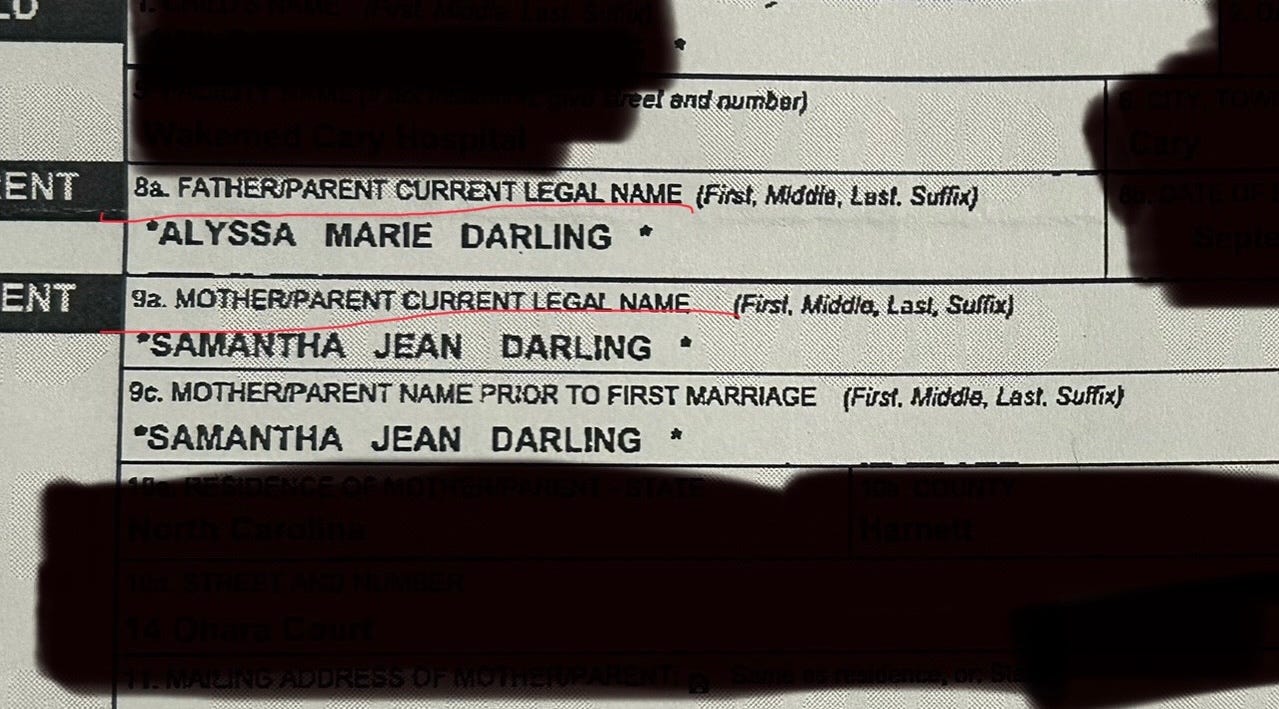

Beyond that, Alyssa is listed as “father” on both of her children’s birth certificates because there wasn’t a place to write a second mother.

Since 2017, married same-sex parents in the U.S. have had the right to write both their names on their child's birth certificate. However, the federal government’s standard birth certificate application form hasn’t been revised since 2003, leaving the sections as “mother” and “father.” To amend this, it’s on the respective hospital to file additional paperwork.

“I asked them what to do, and the nurse was like, ‘Well, you put the father's information,’ and I was like, ‘We're a two-mom couple, she doesn't have a dad.’ And she's like, ‘We're gonna need dad's information.’ And I'm like, ‘But there is no dad.’”

Alyssa circled the option at the bottom of the certificate to be listed as “parent” instead of father, but due to a clerical error, the certificate she received in the mail still says “Father: Alyssa Darling.”

The Physical Toll of Discrimination and Hate

“The experience of the mother during pregnancy directly impacts the health of the infant,” says Bethany Everett, adjunct associate professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Utah. “Tending to mothers is a critical period for public health interventions if we want to improve population health at large.”

While research around queer pregnancy is limited, a 2022 study found that lesbian women living in states with stronger legal protections for sexual minorities had better birth outcomes, including higher birth weights and lower rates of preterm births, compared to those in states without such protections. Conversely, the study found no significant difference in birth outcomes between heterosexual women in states with and without sexual minority protections.

“If you can be fired because you're gay or you can't be legally recognized in your partnership, those things impact your real quality of life,” says Everett. “And those forms of stigma and discrimination can negatively impact the health of the pregnant woman and translate to the health of the fetus.”

“Long-term exposure to distress and discrimination results in chronic inflammation and immune dysfunction,” she says. “It’s not about the person, it’s about the environment that they're giving birth in.”

Angela Thompson remembers not holding hands with her wife when she was visibly pregnant. “We have felt uncomfortable in public, especially in more rural areas after the [Presidential] Election,” Thompson says. “Once, we were at a restaurant in Myrtle Beach, and we weren’t holding hands or sitting next to each other, but people still gave us dirty looks. It’s stressful.”

Unfortunately, providers aren’t always immune to stigma and homophobia. As of 2022, more than one in eight LGBTQ people live in states where doctors, nurses and other health care professionals can legally refuse to treat them.

This translates to negative health outcomes for queer women in the delivery room.

According to a 2023 survey, LGBTQ people were twice as likely to experience medical gaslighting compared to their cis and heterosexual counterparts. When asked to agree with the following statement, “My doctor listens to me when I express concerns about treatments and prescriptions,” 49% of queer respondents agreed compared to 61% of straight and cis respondents.

Thompson’s son was underweight at birth and two weeks early. After an emergency C-section, the baby didn’t cry, which was alarming to the nurses.

“There was not enough of the cord connected to the placenta which meant he wasn't getting as much nutrients toward the end of the pregnancy, which is why he couldn't tolerate labor,” she says. “They don’t know how they missed it. I had concerns about it and I told them to check it earlier but they either missed it [or didn’t check].”

“The whole process feels very disjointed,” says Amy, the birthing mother in New Jersey. “I wish I had been given more information about the risks because this is an IVF baby.”

The couple says that they found out later that IVF pregnancies are at higher risk of hemorrhaging, which also becomes a greater risk when under induction medication like Amy was.

The Same Care but More Expensive: Insurance Exclusion

In addition to not feeling heard, the financial burden of IVF is another stressor that disproportionately affects queer women. A single cycle costs between $15,000 to $30,000, and only 21 states and D.C. have insurance laws that mandate coverage of fertility treatments. One study found that for two-thirds of patients, it takes six or more IVF cycles for a successful pregnancy. That means it can easily cost $100,000 for one pregnancy.

“Insurance coverage and IVF language is an example of just how heteronormative our family building infrastructure still is and how we throw up these barriers for queer folks,” says Abbie Goldberg, professor of psychology at Clark University, noting that only eight states have policies that are inclusive of LGBTQ parents due to language of their policy and requirements for the definition of “infertile.”

Shnell Crymes-Lincoln had to switch employers to obtain insurance that would cover IVF for her and her wife.

“It was astronomical without insurance,” Crymes-Lincoln, who lives in Toledo, Ohio, told Uncloseted Media.

“It was between using our savings for a baby or a house, and we wanted to do everything possible to not have to pay out of pocket.”

Religion and Race

Video courtesy of Crymes-Lincoln.

Crymes-Lincoln is currently pregnant with her and her wife Nesi’s second child. While the couple’s first experience with an LGBTQ-friendly doctor was positive—with Nesi being able to catch the baby, as documented in the video above—they are nervous about their new provider who works out of a Catholic hospital.

“Everything went smoothly [with our first baby’s doctor] … But then my insurance carrier dropped that entire medical clinic altogether, and we only have two medical clinics in this area.”

Both women say they feel more on edge at their new clinic because it features “Mother Teresa statues, prayers and things that are exclusive to certain groups.”

“I feel like you're going to judge me based on your religious thoughts. I don’t feel comfortable displaying affection with my wife, or even calling her my wife there,” says Crymes-Lincoln, who dreamed of “being a mom” as a kid. “We’re worried our birth plan won’t be respected here.”

At their first appointment, Crymes-Lincoln felt like her questions were being “brushed off.”

“It could be because of my race, it could be because of my sexual orientation,” she says. “I'm just worried about the birth, being a Black woman and being a lesbian, we tend to get overlooked.”

“Combined is a whammy,” she says, noting that Black women in the U.S. are more than three times likely to die during pregnancy or childbirth than their white counterparts.

Mothers Just Want to Be Heard

Above all, mothers just want providers who listen to them.

“Just don’t assume,” Sam Darling says. “There was one instance when I was pregnant where a nurse asked if my wife was my sister. It was really awkward. I think healthcare in general needs to do better for LGBTQ community members. Have a pronoun section on intake forms, and ask about your [patient’s] sexual orientation.”

As a practitioner focused on LGBTQ folks, Marea Goodman says representation is essential. “When you go into a fertility clinic and you don't see any other families that look like yours, it can be a really isolating experience.”

In Goodman’s practice, there’s a strong emphasis on prioritizing the parents’ emotional experience. For instance, Goodman allows the birthing mother’s partner to push the syringe during the insemination—an intentional choice to honor the grief that can arise from not being able to conceive privately at home.

Goodman suggests small changes in the system to make queer women feel more supported. “I don't think it's too hard to improve this. If there's one photo in the office of a queer couple, that will make a difference. I think if everyone in the office, including front desk personnel, had training, it would go a long way.”

Goodman also suggests having a list of organizations where folks can connect with other LGBTQ families looking to conceive.

“People feel alone. People feel isolated. People don't see themselves reflected, and society doesn't do that for us,” Goodman says. “We have to create spaces that do. That’s what changes everything.”

If objective, nonpartisan, rigorous, LGBTQ-focused journalism is important to you, please consider making a tax-deductible donation through our fiscal sponsor, Resource Impact, by clicking this button: